21:15 UTC, 12 May 3342

Carolyn woke with a start from confused dream. Something felt wrong. Then recollection.

I'm on Mars. In the future. This isn't just the holiday my parents thought they might have been able to take by now. When I left home I mean.

A future that won't happen, now that we have been Visited. Is that sufficient reason not to worry about all the damage done to the environment here?

She opened her eyes. The room was now lit with a twilight glow, but the expanse of window was still dark. There was no sign of Nancy, but there was brighter light through what she had been told was the kitchen doorway.

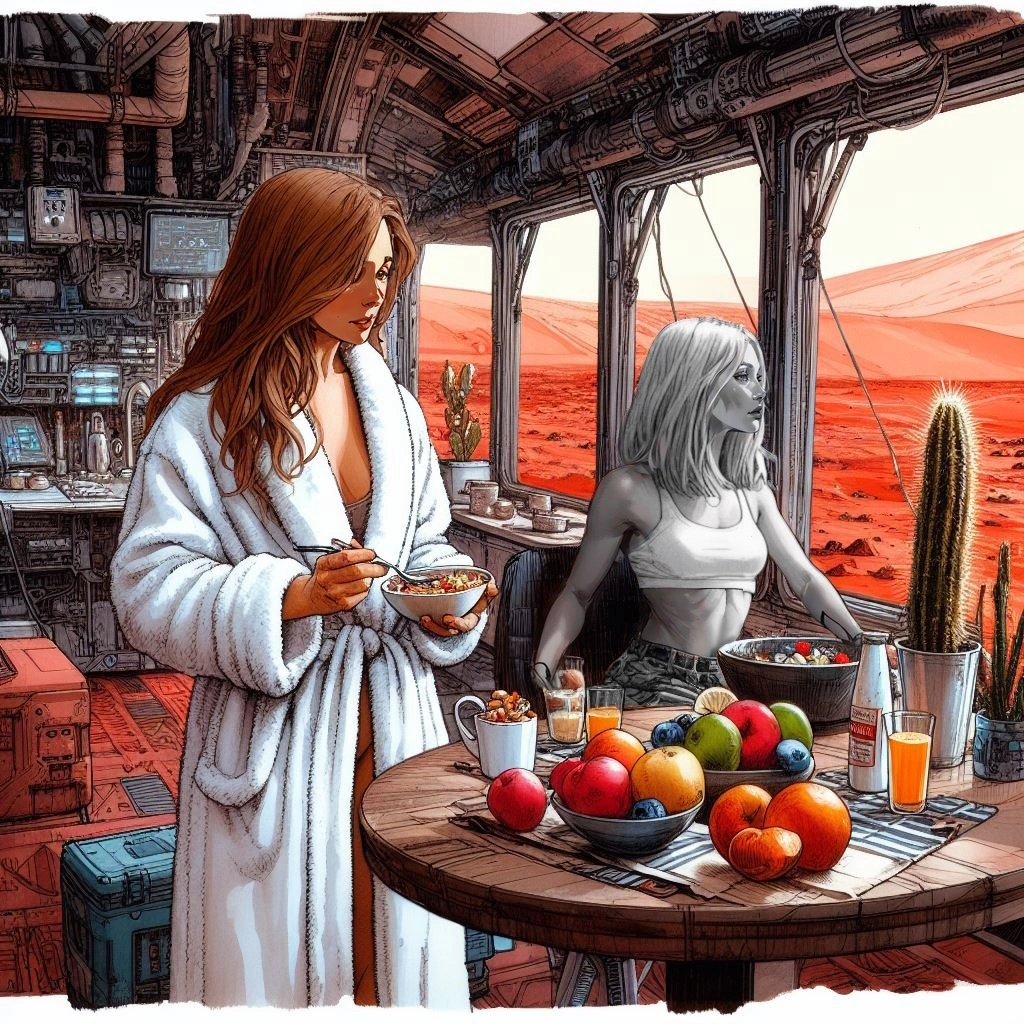

She rolled over and reached out for where she had left her clothes, and touched something unexpected. She peered at it. And saw that folded neatly beside the bed was now a long bathrobe, bulky as expensive towelling, but feeling like cashmere or angora.

She pulled it on, and fumbled for the belt, then realised that it had sealed where she had gathered it around her, and now gave gentle support and restraint as if it had a built-in bra. She could get used to living in this sort of future.

She slipped her feet into the similarly plush slippers, and wandered over to the kitchen.

“Good morning!” Nancy's voice greeted her as she approached. “Coffee's on tap here. What else would you like?”

The room wasn't anything that she would call a kitchen. There was something that looked like a sink, with a microwave nearby, and a cupboard with a mirror-finish top surface on which stood some cups and other crockery, but there was also a full sized dining table, currently set with two covers.

“Uh.” It was too early to make decisions. Pretend it's a hotel, she thought. “Juice, soft fruit, muesli with plain yoghurt rather than milk.”

“Coming up! Just take a seat.”

This morning, Nancy was affecting a hard, military look — urban camouflage trousers, substantial looking boots, and a silver grey muscle vest, and her hair was tied back in a bun. She worked efficiently, taking things out of the “microwave”, setting them by the crockery, and then lifting a whole section of the surface as a tray.

Carolyn watched her bring the breakfast over, already savouring the juice in anticipation. As Nancy set the tray down between the two places at the table, the stray thought struck Carolyn — for all the heavy fluff on her arms, and despite the hard-body look that her current outfit highlighted, this woman from a millennium hence was at least vain enough to shave her pits.

Nancy sniggered.

“Sorry,” she said, “Bad habit strikes again. Shouldn't read minds without asking. But you shouldn't think personal remarks around a telepath either.

“Nothing as crude as shaving — I mean, the concept is scraping with a flake of stone, the rest just implementation detail. No, nor creams or waxes. Simply designed out.

“I'm not just another funny skin coloured carg — oops, sorry, bad word — a differently coloured Pink. I'm a different species to you — Posthomo Taucetii var. lupa — and one of the minor tweaks made was to have body hair function for insulation, rather than scent spreading. Part of the deal was maintaining a neotenous — juvenile — growth pattern. Some of the individual hairs are slightly coarser, and darker, but there are, scalp and brow aside, no dense patches.

“Otherwise, to be blunt about it, it'd be a case of not so much beaver as squirrel.” Image of bushy-tailed anthropomorphic animal.

“But couldn't you just fine-tune it?”

“Why bother? After the major hack required to get resistance to freezing and tolerance of hypothermia, just suppressing unbalanced insulation with a simple switch was simply convenient.

“I could get you fitted up with a similar mod — save on the routine maintenance you need to do.”

“Um, I'll think about it.” Carolyn took a long gulp of the fruit juice. That would be seriously kinky body modification for someone who'd only got pierced for ear-rings and had never gone beyond the occasional henna tattoo.

“What was that bad word you used?”

“Carg. From cargo, as opposed to crew. Think of the worst ethnic slurs you know, that would give the feeling for its weight. And not a word that has been defiantly reclaimed by those to whom it refers.

“The slowboat I showed you took years on the journey. On the way, to monitor on-board systems, then at the far end to survey, select, and prepare the best landing sites, there was a waking crew of a hundred and fifty. To build a sensible economy, there were tens of thousands of people in suspension, to be revived after landfall. Our cargo. Not even passengers, really.

“We knew we were heading to a world locked into a stable extreme ice age, so the Crew were given aggressive mods suited to unsupported existence in the environment we'd encounter. The colonists weren't. They could do like people had always done best and adapt the environment, indoors first, and by terraforming in the longer term. And besides, some of the Crew mods were incompatible with the suspension process they went through.

“It ended up a class thing. We were — my ancestors — the genetically superior master race on the planet as we found it, and could prove it. Despotism and oligarchy came naturally.

“That was why I said that the family had been described in terms you'd consider similar to National Socialist, though it was more like a traditional aristos and peasants set-up with a smattering of implicit apartheid.”

She paused to take a mouthful of coffee, and Carolyn took the opportunity to start serving herself some fruit.

“It was not one of the high points of human history, even if it had started out as simply the sensible thing to do for the Crew to stay in charge. And even though it only lasted a few decades before we had the infrastructure in place to liberalise, the stigma has stayed with for more than a millennium.

“It wouldn't have been so bad if the charge had been the right one, that we had managed to re-invent Africa from a couple of centuries earlier. Those we relinquished authority to were worse than us in many ways.

“It caught us again during my lifetime, and it's only in recent decades that we've found a new world to set down on. The whole clan, the castle, were in flight for fifty years.

“I shan't be sorry to divert from that path.” She had been looking distant as she told her tale, but now focussed on the instant. She looked at Carolyn and smiled.

“You're awake a bit earlier than I'd set the lighting to come on fully, so there's no need to rush your breakfast. Oh, and no need to worry about waste — it can all be recompiled.”

“I'm not so worried about that as I am about what exactly this is that I'm eating. I mean, it all tastes good, but I've not seen any of these fruits before!”

“The soft, pale green is gageapple, the pale yellow chunks are lemmelon, and yellow-orange stoned ones are aperies. None of them are terrestrial — give or take the fact that there was a lot of mixing of basic biochemistry in the deep past — but they're all popular amongst humans and descended species in my time.

“The muesli is based on Earth-descended grain and nuts, and the yoghurt on generic milk. Generic meaning averaging out the make-up of various ungulate and human milks to get the nutrient balance before the simulated fermentation.

“You'll be glad to know that the compilers omit the natural poisons that don't have any beneficial side-effects.”

“I suspect that I didn't want to know any of that. I'm not a food faddist — but I do buy organic and oppose GM because of the pesticides and effects on the environment. But then this won't have had anything to do with the environment, will it?”

“Well, the raw materials are much recycled cometary organics; there's no agriculture on Mars outside of greenhouses.”

“Like where we arrived? That looked like it had just ruined the unspoiled places with scrubby grass, like this place has scarred the landscape.”

“So it should all be left untouched? Nothing would come of it before the Sun burns out. If you want the virgin ecosystem, we can synthesise it by the bucketload. And in a thousand years, this architecture would count as heritage — like the city of Petra, or the Central Asian Buddhist rock carvings.”

“That's very cynical of you.”

“Practical, rather. But you can console yourself that it won't happen at all if I'm successful. I don't expect that the other nearby waves of expansion will stop here. Not if there's an Ascended world next door.

“Nor will humans touch Lindisfarne — τ Ceti III, where my family rose to notoriety, or Starbow, where we went next. You don't expect me to stop all the other intelligences out there, I hope.”

Carolyn felt blocked. On her home ground, she would be able to argue her case more forcefully, but having to deal with might-not-bes, and aliens went beyond the issues she had to deal with in her normal life. If the human race could be made to grow up, to be something better, perhaps that would be the best that there could be in this imperfect universe.

This was too much responsibility for one person. She felt she maybe had a glimpse of the pressures that Nancy was working under.

“Pretty heavy stuff for breakfast, I'm sorry,” she apologised, “The food tastes good, however you made it, and I guess it's ideologically sound, even if it's not grown traditionally.”

And she set to clear her dish.

22:00 UTC, 12 May 3342

“The train out of here.”

Nancy indicated a capsule, maybe the size of car, a brushed metal cylinder sunk half its depth in the floor of this remote rear chamber. Part of the cylinder had rolled open, to steps that gave access to a white interior with blue-grey bench seats that faced towards the narrow centre aisle.

Nancy bounded in, and stood, offering her hand to assist her boarding. Carolyn followed, and sat herself down with her back to the doorway, facing her guide.

There was a faint noise behind her, and a vague sensation of acceleration, and they were plunged into darkness, relieved only by the comparatively dim interior illumination.

Sitting there in the darkness, with no real sensation of movement, just a very faint rumble and rocking, Carolyn suddenly felt quite at home. This was like the Underground had been when she was a child, before all the crowding and the homeless. More, how it should have been, all smooth lines, seats that were not worn, no gum, or adverts. The very familiarity, or likeness of, made it hard to remember that she was travelling deep under the surface of Mars.

The evidence of that strange future world was with her, though. Having finished breakfast, she had watched Nancy place the washing up and leftovers on the worksurface, where the pile had simply started to sink into its mirror sheen.

And then clothing. She had remarked that she couldn't very well go gadding about the Universe in just a dressing gown and slippers.

“Well, what do you want to wear? Same as yesterday, or something different?”

She had hesitated. What did she want to wear? Something that would give her confidence. Mentally, she began to review her wardrobe, then stopped, distracted by a feeling of things crawling on her skin. She looked down, and saw that the dressing gown had turned off-white, and was less fluffy.

“Just think clearly,” Nancy advised, “and it will build to fit. Hold on to part of the collar, and it will stay in one shape while you consider. It assumes that you only think about changing when you really want to or need to — armour, environment suit, whatever, and may not have a hand free.”

Carolyn grabbed the sort-of sweatshirt collar of the now nondescript garment, and thought again. Suit? Formal wear? Or perhaps…

Why not? Sure it was going on fifteen years since she last did that sort of thing for real. She relaxed her grasp, and remembered, and improved.

A black, silky long-sleeved T-shirt with the same intrinsic bra effect as the dressing-gown, decorated with a large, pink Venus' Mirror, with a clenched fist in the circle, black leather trousers, soft and tight as a second skin, though growing those and the silk panties under was seriously creepy, like being groped by what she was wearing. And to finish, calf-length, low-heeled black leather boots with cashmere-like socks. Her old Guardian Angel outfit, apart from the beret. No beret, she decided.

She might be older and slower, but the uniform gave her the confidence to feel she could kick ass where needed.

“What now?”

“This way,” and Nancy led her back through the bedroom, towards the liftshaft. Halfway, Carolyn remembered her handbag, sitting on the table by her bed, her last connection with the world she had been born into.

“Wait, my things!”

She hurried over and picked it up. The mid-brown leather didn't go with the rest of her outfit.

“You want a couple of blocks of cloth-stuff to work with,” Nancy suggested, “they're in the drawer.”

Carolyn pulled the drawer open, and found a number of bricks of translucent greyish waxy material, about as thick as a DVD case, and about two thirds the size. She picked one up in each hand, and thought of a black belt purse, and added a pouch containing a pair of aviator shades.

Material flowed in her hands, and her sleeves pulsed as she grew the accessories. Transferring keys, cards, and her other impedimenta took a few moments, and then…

She took another block, concentrated, and settled the soft black leather peaked motorcycle cap on her head, pulling the peak to settle it into place.

“I'm ready,” she admitted, slightly ashamed of playing dress-up.

Nancy smiled, and led her down the liftshaft, and back into the depths of the cavern which she remembered from the previous evening, where great cat-caryatid statues held up the cavern ceiling over an indoor garden of trees, and rows of odd looking bushes, and flowing water, fairly thick with green algae.

“Simple biological environment control. We're heading all the way back through housekeeping and into the subsurface access.” And so to the sterile back room where the train waited.

The end of the journey came without warning, a very gentle jolt, and light outside. The door slid open, where a voice announced “Olympus Down station, services terminate here.”

“Our stop,” Nancy commented. She clambered out, looking weary.

“Something the matter?” Carolyn asked.

“This is where I have to be on best behaviour, rather than being queen of the hill. That takes work.”

Carolyn followed Nancy's lead, out into the hall. Where she had been sitting, facing away from the door, the full scope of the place they had come to became apparent. There were echoes of the RER levels of the Gare du Nord — if only on the simplistic level of being big, a railway terminus, and, above all, slightly, indefinably, but definitely, foreign. Unlike a normal main rail nexus, however, this one was quiet, deserted, and not harshly lit. Nor were there any signs of advertising, nor litter.

The train they had arrived in could now be seen to consist only of the one capsule; at other platforms, longer trains waited, silent.

“Are all of these here just for you?” Carolyn asked.

“No, this is public space. It's mostly disused now. The terraformers gave up centuries ago, when it became simply easier to find a more suitable planet to make home. Perhaps if we hadn't found other starfarers willing to trade us the twirl, a first usable stardrive, then the Mars Firsters may have stuck it out. In a history where a couple of races had Ascended completely, the trains might be running busy all over the red deserts.

“Come on, this way.”

Rising from the platform, a ramp ascended to a level above; slightly blue, against the overall grey-cream colour of the rest of the station. As she placed her first foot on the ramp, Carolyn became aware of its texture being different, too. The platform had been firm and smooth, like fine grain concrete; this gave underfoot like a layer of fresh snow, and as she carried into the next step, she felt a tugging at her feet.

“It's moving,” she called out, startled, as she briefly windmilled her arms to catch her balance.

“It's just a slideway, a fancy moving walkway, something too familiar to remember to warn you about. I don't think there are too many more big but subtle things like that to meet. There aren't too many smart-matter devices like these in public use,” Nancy apologised, “ I'd better tell you now that we shall be meeting some non-human intelligences here, not just little grey people from Outer Space like me!”

Carolyn didn't feel to reassured. She remembered seeing Alien as a student, and being quietly terrified of the dark for some days after. Even allowing that whatever it was that they would meet was civilised, she had dark forebodings of something dark that slithered and made insectile clicking noises.

Above the rail levels, where the slideways deposited them, was something generically familiar; an airport style checkpoint; three booths in gaps in a transparent partition that had space for dozens. It added to the run-down, faded air of the rest of the station. Nancy halted, apparently waiting for something.

“Why are we waiting?” Carolyn whispered, feeling too conspicuous in the wide open space.

And then the question was answered. From beyond the partition, something was approaching, something shambling, in orange and black, that she couldn't rightly form into a coherent whole. It entered one of the booths, and arranged itself, looking rather like a traffic cone — but a dull yellowish one — sat behind the desk.

A stream of hooting, farting noises came from the creature, and after a short interval, a neutral, but human sounding voice spoke out on top of the noises, but in some incomprehensible foreign tongue.

“Kyu go pomo zi, tclenwofsa pesilnoshi?”

Nancy strode forwards, and Carolyn took her cue from that, following a few paces behind where the heavy boots clapped on the floor.

As they came up to the creature that at close hand looked more like a carrot coloured cactus, complete with ridges and spines, garlanded with a crown of very human, bright blue eyes, Nancy replied in similar sounding gibberish.

“Ching bol hameribol! Gosa pekun bupren tweenbol.”

The creature rocked back a little, and reached a limb or similar mass across the desk.

It hooted again, but this time the voice that joined in was in oddly accented English that took a little work to key into.

“My apologies,” it began, “we should now all be able to understand one another. Is this so, lady?”

Carolyn felt Nancy looking significantly at her, expecting a response.

“Um, just about. I have to get my ear in for the accent.”

“The translator should adapt to a consensus as it hears you speak.

“Well, Lady Wolf, what is your pleasure here today?”

“I want to take up the flight plan I optioned for today, along with my companion here. She's the back-time contact that I filed with the Seraphim. Carolyn Wilson, from pre-Ascension Earth. You won't have her identity on file.”

Carolyn saw the eyes, those on her side at least, swing to fix on her. A bunch of tendrils as long as fingers, but thinner than pencils waved and rippled at her in something that she interpreted as beckoning, and she stepped up to the desk.

At this proximity, she could smell the creature, an odour like dead flowers and bad sex, and, when it spoke, determine that the hooting came from its central mass, as, surprisingly, did the human voice.

“Well, Mistress Wilson, it seems that you are a newcomer. Please place your hand on the illuminated plate, so we can identify you through our system.”

A patch of the desk started to glow, and, holding her breath, and not trying to look too closely at the creature, Carolyn leaned forwards to place a hand on the light. There was a brief scraping feeling, as if sandpaper was being run under her palm, in all directions and none, and the light blinked off. Almost instinctively, she recoiled from the proximity of the unknown, with a slightly voiced gasp.

The creature paused, and then looking up from the desk, fixed its attention on Nancy.

“Is this woman a Feral?” it asked.

“No, she's from the past, when even a single point nip was high tech, very few people had even those upgrades.”

“Well, then, Mistress Wilson, I would suggest you seek some medical attention without undue delay — in the next decade or so.”

“What? Why? What's wrong?” Carolyn was suddenly seized with panic. She had started to see near contemporaries, some even younger than herself, dying from cancer. Had something been detected?

“It just means that you'll be getting noticeably old by then. But we can get you an upgrade to avoid that.”

“Aren't we supposed to be getting whatever it is you need to do done sooner than that?”

“If all goes well it will still take years. And you'd function much better if you had the vitality you had when you last wore that outfit, wouldn't you?”

“Yes, I suppose so.” She looked around. “Is there anything else we need to do here?”

“No,” the creature replied, “you may proceed. Welcome to the Ascended Territories.”

It moved back from the desk, bobbed up and down, a gesture which Nancy echoed, and then shambled away. When it had disappeared whence it had come, Nancy turned to her, looking up with a concerned expression, and said, “Well done! They sent out one of the moderately weird ones, and I would guess that was deliberate — a test of sorts.”

Carolyn took this commendation with surprise. She let out the breath she'd not realised she had been holding, and shuddered briefly. She felt a chill sweat on her brow. Summoning a weak grin, she smiled back.

“Why, thank you. Now can we go — the smell will make me feel sick soon.”

“It was shedding pollen, and that's liable to trigger an odd response when you're not habituated.

“This way to the next ride.”

22:30 UTC, 12 May 3342

Mars receded beneath them, now visibly a globe, a fat brown crescent moon magnified but diminishing. Carolyn could see a great scar stretching out of the night and across the illuminated face, intensified by the low angle of the light, but fading towards the late morning and the limb. The low morning light also showed the peak of a volcano, but everywhere, craters like a moon.

Above, the light of Deimos showed no sign of change, though clearly it must be slightly larger now.

“We're about half-way,” Nancy, floating next to her, spoke to reassure.

This was indeed not what she had expected by way of space travel, floating — speeding at goodness knows what speed — with no spaceship, no spacesuit, apparently surrounded only by the emptiness of space.

When they had passed the checkpoint, Nancy had led her through more airport-like corridors, where the pale blue moving walkway stuff had whisked them along. After some time the way emerged above ground, running in a transparent tunnel.

Outside, the sky was black, but the soft light of the tunnel showed the rough terrain beyond in shades of grey and rust. Ahead, harder to see for the tunnel, there was a cluster of bright lights, and from its midst, something rose into the darkness until it was lost to sight. Carolyn strained to tell what it might be, this tower that didn't quite look solid, misty somehow.

As they approached the lights, it became more difficult to see the tower against the strip of light that ran along the apex of the tunnel. And then they were there.

The roadway opened out into a wide circular space, swirled them around its perimeter, where Carolyn could see that it was formed from a wire mesh, the cables not as thick as her wrist, and a dull, almost greasy, grey in colour, and the openings large enough that she could comfortably have walked between them.

Outside, lights shone on a number of deserted seeming domes. A feeling of unseen energies hung over them, a tension that Carolyn could feel in her bones.

“A little while yet before our slot. We'll stay in this holding pattern, circling around, until it's time to move. As there's so little traffic here these days, the system isn't kept running full time.”

The circling continued, and then suddenly became a tight inward spiral. Underfoot, a deep powerful rumbling began.

“What's happening? When are we going to board the spaceship?” Carolyn had a sudden foreboding that thing were not going to the script she had expected.

“No spaceship! This is a lift!” Nancy's voice was almost lost in the growing roar. And then silence fell.

And the ground fell away, the lights around them shrinking and diminishing below them.

Minutes passed, and the sun rose over the eastern horizon, then the sunlit part of the planet started to come into view below the sun.

Now, more than half-way to the top, it seemed to Carolyn that Mars was falling away even more rapidly underfoot.

“We are going to stop, aren't we?” she asked, all her usual travel anxieties about making connections boiling up, though she knew that here she just had to sit back and try to enjoy the ride.

“Yes, but not just here,” Nancy replied. Carolyn didn't care for the enigmatic grin that accompanied the remark, but followed the gesture to look up.

The pinhead of light above had become a tiny ring, and in the ring strange fire seemed to burn. In a sudden rush the ring expanded. There was a rush of green and gold flame, and then…

Ahead of them an enlarged full moon. It drifted past, as they slowly spun about. A quarter turn, or so, and some strange crystal mist, again, and a dark disk against the stars, rimmed in red, about as large as the moon, and then another of the mists.

“Earth, Moon, and some, uh, things, stuff, also in the Moon's orbit. They aren't anything we can understand. Earth is bad enough in this epoch.”

“So, do we hang around here, then?”

“No. Watch. We're heading back down to the bottom of the well.”

Indeed, the disk of the Earth was growing, like an oncoming train. Carolyn was not letting herself worry about things like how there was air to breathe here, but the approach that would all too soon start to feel like a fall grabbed at her guts and twisted.

The tumbling had now stopped, leaving her facing the drop, which made things worse, and as her eyes adjusted, she began to make out features on the face of the Earth under this full Moon, oceans dark, continents lighter, and clouds almost luminous. But there was something that looked wrong, different, though she couldn't pin it down.

“Hint: look at Africa,” Nancy suggested. She stared, but could not place what was changed. Then it clicked. The north of the continent was dark, where not cloudy, and the equatorial regions bright with desert.

“Not the Earth you left, but the Earth that your activities bequeathed. Something I'm trying to correct. There are other changes, all the way down. You'll see.”

That didn't sound reassuring, but Carolyn continued to look. Under the cloud, much of Europe seemed pale, and as their descent took them north, she could see that Britain had changed, though at least not as much as at the start of Revenger's Tragedy, but the sea was pale around Scotland, and the east coast eaten away. The Wash had devoured most of East Anglia, where the engorged mouth of the Thames had not done so.

“The worst of both worlds. Sea ice, even in late spring, and the rebound from the previous Ice Age compounding rising sea levels. Eventually, the glaciers will see-saw London out of the North Sea again.”

Now the ground was not a map any longer, it was real land and sea, and there were no lights of towns, or roads, or cities, and they were falling towards some part of eroded England, north of that bloated Thames. Carolyn closed her eyes, and wrapped her arms about her head to shut out the imminent collision.

Crushing weight descended on her, and she waited for the end, but as the seconds ticked away, nothing happened.

“You can open them, now. It's just the gravity. You'll have to get used to it again,” the remark soft, as was the hand on her shoulder. She stood slowly, and uncurled and looked.

They were on a grassy hilltop, lit by the full Moon shining down from a cloudless sky. A gentle breeze blew, chill on face and ears, but otherwise the thin clothes were more than warm enough.

Below the hill, strange organic forms rolled away like a frozen sea, and from the mass, ancient stone buildings, like churches or cathedrals, rose. Above the strange mists she had seen from space accompanied the Moon, lower in the sky to east and west. There was a smell of flowers on the breeze, and a distant tang of smoke.

“You can't see them from here, but there are settlements nearby. They stay away from the old town, down there, but the bridges remaining just upstream from here — there's a river under all that — make this an attractive place to settle.

“There was a genius loci animating the mass, something of similar magnitude of intelligence as humans, but otherwise incommensurate. Not malicious, but not a good neighbour — too weird. It's quiescent or fragmented now, but tradition keeps people away.

“Otherwise they'd've been plundering the old buildings for stone. As it is, the mound here makes a useful place to wait for our pick-up.”

“Is all the world like this?” Carolyn found the place disconcerting, the growth, whatever it was, like a living thing, that had eaten an antique British town.

“Not all. Western Europe is sort of similar. Africa is not too different from how it was ten thousand years ago. Even parts of these islands are much as they were maybe four thousand years ago, back when Rome was new founded.”

A bleak thought filled Carolyn. All she had done, was to do, had been futile, erased casually by the passage of years.

“Not all,” Nancy began again, “Look!” and she pointed, indicating a direction behind Carolyn, away from the ruined town.

Something dark was floating high above them, rising silently out of the north. The Moon shining on it seemed to show the gloss of leaves, and the upper part had the organic shape of calabrese or rainforest canopy as she had seen it on the TV. Below, darkness and shadow made the contours of it indistinct, though there was a suggestion of roots in amongst inverted skyscraper shapes.

Slowly, it approached the zenith, Carolyn crouching to better keep her balance as she craned her neck to keep it in view, as it moved up, and over, and past, halting only when its ponderous shadow covered them. And the magic filled the night, as a blade of blue fire reached down from the looming darkness above, to touch the ground by their feet.

Insubstantial as the moonlight, it seemed, and burning an icy blue, like midwinter moonlight as well, like the obscured Moon was focussed into this, this stairway to the stars. For Nancy had now set foot on it and was starting to ascend. Carolyn hesitated, swallowed hard, and followed.

Though the slope seemed more insubstantial than mist, though more so than the light, it bore her weight, and let her climb, sliding upwards, up to the darkness floating up above.

The silence of the night was broken only by the sound of her pulse, her breathing as she climbed, the so soon unaccustomed weight dragging her down. Then, as she ascended, there was the sound of the wind, sighing in the trees. Were those really great branches covered in full leaf, that grew from this island in the sky?

Nancy was now far ahead of her, and she had no breath to call, and no sign that her thoughts were being overheard. How had she managed to get so far ahead so quickly, when she had had so little time? Carolyn turned, and looked back, and saw that the ground was now far below, showing that the climb had been more than simply what her legs had achieved. Without any indication, this had to be another moving way, though as Nancy still strode on and up, Carolyn did not dare rest to let the ascent just happen.

As they climbed higher, some more details became apparent where the floating island was silhouetted against the Moon-bright sky. Around the waist of it, just below the organic, tree-like mass, a platform, broken in places, extended, and it was there, above the dangling mass of roots or crystal, that the Moonbeam terminated.

Minutes later, the end was in sight, Nancy standing at the edge, and then Carolyn too was standing on something that seemed more like stone, panting slightly in the gloom. She looked up, at the looming, rustling mass, which sighed gently, like the rushing of a distant ocean, and which filled the air with strange vegetal and floral scents, and felt some sort of grander movement about it. The sudden appearance of the Moon around the mass, showing it like the forested slopes of a mountain, told of a slow turning.

“Soon we will have some more light, and then we have to go inwards and up some more, and this time the work will all be done by our own muscles.”

Such light as there was, began to show unwelcome detail. Where the stood was a ring of weathered stone, maybe a couple of yards across, separated from the main body by a wider gulf through which cautious peering showed the landscape far below. Nancy for her part seemed unconcerned, and with the growing light, set off around the ring towards the Moon-lit side.

Carolyn followed, carefully, terrified by the yawning drop on either side, and then balking as Nancy hopped down from the ring, onto a shadowed spar leading inwards. When she had reached the same place, Carolyn paused, and she could see the silver hair gleaming in the light as her guide went on. Sure of the long descent, she carefully lowered herself from the ring down into shadow, and with relief, felt firm stone beneath her searching toes. Better yet, it took her weight, and she at last stood with the ring about waist height. Then, slowly, she started forwards on the shadowed way, until her leading foot went down further than expected, and felt something yielding. Off-balance, she stumbled, and sat down hard on the stone, crying out as she did so.

“Help me!” she called.

Footsteps rang on stone as Nancy ran back, then stopped a few yards away. A smile broke out on her face as she stepped forwards the last few steps.

“Don't walk on the grass,” she joked, and extended an arm. Carolyn reached out to feel. It was true — she had stumbled at the edge of a sunken area of soft grass, or something akin. Grinning ruefully back, she took the proffered assistance, and hauled herself to her feet. On impulse, she did not let go, but took Nancy's hand as she started off again.

“A romantic walk in the moonlight?” Nancy laughed.

“Just making sure I keep you in sight.” I'm too sore just right now, she thought. She was feeling bruised and shaken from her tumble, sure she'd be developing a magnificent bruise on her bum. And more than a little terrified still.

It wasn't just the height, the yawning unfenced drop just a few steps away on either side, it was this whole creepy roller-coaster ride through the future. She still shuddered at the thought of the thing they'd met on Mars, what, just half an hour ago or less. What other unspeakable shambling things from out of space and time would she be forced to confront here?

Holding on tight to Nancy's hand, the two of them continued along the spar towards the central mass, Nancy, on the left, closer to the drop, Carolyn staying near the slightly sunken grassy bed that ran along the middle of the spar. At the inboard end, there was another step, up this time, and really no more than a few handsbreadths high, to be taken in a careful stride.

There, beyond the narrow stone rim stretching left and right as far has could be seen, a lawn, looking well kept, spread in the cold light, and beyond that, rippling like scales, and sighing, the leafy branches of trees that covered the slopes that towered above.

Still holding Nancy's hand, Carolyn followed across the open space to the shadow under the eaves of the trees.

“What is this place? What are we looking for here?”

“It is probably some conduit for the Ascended by which they maintain some toehold in the world of matter and forces. I don't really know, it's just the best guess of the theologians,” Nancy spoke quietly, just above a whisper, “One of the Seraphim will find us soon, there, in the shade.”

“It won't be like the…” words failed her.

“The jumped up starfish that put the wind up you at Olympus Down? No. The Seraph will be different, but no less terrible.”

They were under the outermost limbs by now, and Nancy stopped just at the point where they were entering the full shadow of the leaves, punctured as it was at the periphery by disks of light let through by gaps in the cover. The wind stirred the branches overhead, and it sounded like breathing. Their footsteps had stirred up some dry dust, here where the grass failed, and the earthy scent of ancient woods filled her nostrils.

“Here it comes. Look!” Nancy pointed, and, following her direction Carolyn saw something move. A pale splotch that had markings on it, moving at above head height the face of some elongated misshapen thing, no doubt, and she quailed. It approached a spot where the Moon shone down clear through a gap maybe a foot or so wide, and she was ready to clench her eyes shut against eldritch horror.

And then it came out into the light.

Stalking elegantly along a branch, a cat, shaped and patterned Siamese, its colour hard to say. It drew itself into a Cheshire Cat pose in the spotlight, and fixed her with wide eyes, deep pools of darkness, where hidden things were suggested by the Moon's rays.

Yes. Once there was a cat, something that was not a voice purred in her head, Did you think that only our servant apes participated in the Ascension? There are many Ranks and Orders amongst the Ascended, though fewer than might have been.

And there is also a niche for a rôle akin to bodhisattva, one who could ascend, but pauses to assist others, when dialogue is required with natural beings. Else I would be following the Most High on the path to infinity.

The wedge shaped head turned to Nancy.

So this is to be your herald, your intermediary.

“Yes,” Nancy spoke aloud, “she was a usefully significant actor in this history, and could be more.”

This will be a hard and perilous road. You wish her to be fortified?

“Yes. This is an investment of importance, to be protected.”

Have you told her what you are asking for on her behalf?

“Not directly. Here and now is about the first time she will have seen for herself what sort of changes must come.”

“Hey, I'm still here,” Carolyn interjected, annoyed at being cut out of the talk about herself, and not at all certain about what was going on.

Then I suggest you explain and the Seraph turned deliberately to groom itself.

“Yeah, what the hell is it you are cooking up for me? What peril did it mean?”

Nancy turned to her, looking abashed.

“It's a difficult sort of thing just to drop into a conversation. You know I want you to help me bring the Ascension earlier than it would normally have happened. And from what you have seen and heard, you know that it represents the end of the world, at least as you — and I for that matter — understand it.

“It may be inevitable, but that isn't to say that it will not be resisted. And those who are seen to be assisting to end the world will be obvious targets for anger. That's how you died, long before the Ascension actually took place, at the hands of terrorists who were resisting what they called the New Æon. How much that was just that even turn of the century tech threatened their illiberal, misogynistic, status quo, and how much was of something more, some delayed chiliastic dread, the records we have are unable to distinguish.

“Here, now, the Ascended are willing to give you an upgrade, so you would survive that and worse. They can rebuild you.”

“They have the technology. Better, faster, stronger, all that.”

“Yes, of course they have the tech… Oh, I see the reference. Yes, better, if not particularly stronger or faster.

“It will be a biological replacement, not crude electro-mechanical parts. Posthomo perdurans, var. Wilsoni a far better model chassis than mine.

“For a start, though we hope it won't come into play, it lasts longer — I need routine maintenance every few hundred years; perdurans is designed to get by for thousand times as long without need for medical intervention, short of managing recovery from severe trauma. For our purposes, it means you'll be young and in your physical prime all the way to the Ascension.

“Next, health. You'll have a metabolism that copes with a broader range of food, including things that are mildly poisonous to you as you are now, that burns off excess intake above a safe set point. Your immune system will be an even greater defence in depth, with cross-checks against auto-immunity close against the Gödel limit. It would sneer at AIDS, were it not for the fact that you could no more be affected by it than wheat can get rabies. It will protect against rabies, flu and other diseases that are generic against a range of mammals — infections specific to genera homo and pan — hominids and great apes — will simply bounce.

“And you will be tougher and more resistant to physical harm. It will be possible to kill you, but to be sure would take overkill — dropping a skyscraper on you, or sustained incineration would probably do. So if you're ever in a tall building that's on fire, jump as far clear as you can and starfish — 200 kph on concrete is survivable for you now.

“Hell, you could be a suicide bomber, and while you wouldn't be able to walk away, you would survive. Damaged, in pain, needing some medical support to get out of bunker mode, but alive and able to regrow.

“Plus, as part of the process, you can take almost any cosmetic upgrade you can think of, except that we do need you still to be recognisable as yourself. You won't be able to prove your identity with a DNA test, after this.”

“You make this sound like buying a new car, all these features. Can I have one cosmetic change? I want new teeth, without all this metal.”

“Sure — dental records won't work either — those come as standard, every decade or so the old ones are partly reabsorbed, partly fall out, and are replaced. And while keeping looking recognisable, you'll look and feel maybe fifteen years younger, no sagging, the grey hairs growing their original light brown.

“How about adding chromatophores, so you can be as tanned as you want to look, or have tattoos that are there only when you want them?”

“Ah, uh, ” this was strong stuff, a true temptation. Did she dare? Would it be sensible to decline, if she could trust the story of how she might die? “And if I say yes, could I also have the, uh…”

“The body hair hack? Nothing but conventional head hair?”

Carolyn nodded.

“For what it is worth, fertility under conscious control is part of the package too, unless you actively want to be a worker bee like me, and need to have eggs grown specially from stem cells if you ever want any. On the other hand, not only didn't you fit in any child bearing in this history, but you won't be interfertile with homo sapiens after this.”

“I need to think about this. If I agree, does it just happen by magic, or what?”

It is physically possible to just rewrite you in place, by using the quantum cheat codes of the universe, but I do not have the authority to use such capabilities. It would some time — days — as you are rebuilt cell by cell. For comfort, sedation is recommended.

“Would I still be me?” as the Seraph had rejoined the conversation, she demanded response from it directly.

Are you still the you who asked the question? Are you still the you who settled down to sleep last time? Are you still the you who was thirty?

Consciousness will be interrupted, but no more than sleep ever does. And there will be more material in common after than you share with your thirty year old self. This froth, this foam that is consciousness has no integrity to be preserved, but memory, personality, behaviour, those will be maintained intact. You will be no more different in that sense after the upgrade than you would be without.

09:00 UTC, 24 May 3342

“I'd suggest wearing something long-sleeved when you get back home,” Nancy suggested.

The sun was streaming down on the lawn outside the white room where Carolyn was standing, filling the space with clear cool light. On one of the side walls there was a full-length patch of mirror, an apparently seamless change of surface quality, and she was stood in front of it, admiring herself.

She had reformed the plain white smock which she had been wearing on waking up into a near facsimile of the outfit she had worn for her arrival on Earth, though this time the top was short-sleeved, and cut short to show off her midriff.

She stretched out her arms and admired them — the elbows taut, the muscles sharply defined, but without being covered with the obvious veins of a fully ripped look. Her bare belly too, flat, with just a hint of six-pack, rather than the slight bulge of approaching middle age. And the face that looked back at her was the one that ought to be there, more mature in appearance than the twenty five year old she had once been, but not as lived in as the almost forty year old face she had still not been reconciled to seeing there.

She wriggled, and watched herself in the mirror.

“This is rather more showing off than I'd care to do back home,” she replied. Including rather more camel-toe than she'd want to show too, she thought, the tight leather trousers looking very much like spray-ons. But here, now, she wasn't going to admit it — at least not out loud, even though her thoughts may not be secret. She would have to learn how to adjust the cut, or just resort to her own old, dumb cloth wardrobe.

“I'll worry about that when the time comes. Right now, I'm just getting used to the change. When I woke up just, it felt like I'd just woken up feeling better after having had the 'flu. And I really can't believe I'm not going to have to endure some masochistic diet and exercise regimen to keep this figure. It's how I wanted to be when I started training, but never managed.”

“All part of the fine tuning — fitting the changes to your idealised self image. If you've finished admiring yourself, let's go outside and enjoy the fine weather.”

Had she finished admiring herself? She'd never figured herself as a narcissist, but this was different. All that soul-searching back in that moonlit garden seemed distant timidity now. The fact that this body felt slightly unaccustomed, even the new, even, and — she checked by going up to the mirror and opening her mouth wide — filling-free teeth that weren't quite where her tongue expected, reassured her that the flesh had changed, and not her own innermost self.

And all so swiftly. Or had it been? It seemed only a matter of minutes, maybe an hour ago that she had given in to vanity and fear of her own extinction and assented. Following the Seraph-cat, she and Nancy had been led under the trees, and up to a building seemingly carved directly from the rocky core of the flying island, where there was an artificially lit room, containing only a bed-like contraption, almost like a cell from a Japanese coffin-hotel, but opening like a real coffin with a transparent lid.

You climb in, and lie down. There is a tube by your right hand. Drink the liquid. Then you will sleep, and awaken after the upgrade is finished.

She had felt self-conscious getting into place, and then taking the tube. This, then, was the crux. This was where she had to decide if she trusted any of this. And yet why shouldn't she trust on the basis of what she had experienced in the last few hours?

She picked up the tube and looked at the silky white liquid. Put it to her lips, and drank. A taste of blood and sex filled her mouth, and then everything had swirled and vanished.

And then, just minutes ago, she had woken from refreshing deep sleep, in a more conventional bed. The first moments of consciousness had been pleasant ego-muted Zen neutrality, then self-referential joy at being conscious at all again, the swift review of memory of what had passed before she slept. Then throwing off the covers, and lifting up the smock, to see, to assure herself by touch, of the reality of this new firm, lean, smooth, young body she now wore.

“OK, Sleeping Beauty, I know you're awake. Get yourself dressed, it's a wonderful day today,” Nancy had called from the next room. And so here and now.

The cool, the freshness for all the dazzling sun told her that it was morning here, though her body, her gut, had no opinion.

“What time of day is it? And more importantly, what time of day should I think it is?”

“Morning. And you're synched with local time now, for convenience while you were out. I've been working on resources for when we go back, and I synched up with chemical assistance. You can indulge in breakfast now, if you want. No guilt, remember — you'll stay at your current, optimal, weight. Though you'd have a shock next time you weighed yourself, if I hadn't warned you now that you're a few kilos heavier than you were — the best part of a stone, if you still think in those units. Extra muscle mass, and some denser, bio-ceramic, parts.”

“No, I'm not really hungry just right now, and I'd rather stay trained out of being greedy,” she paused, thought, hesitated, then asked, “How long was it I was out? I mean, I am due, was due,…”

“Twelve days. But don't worry. Listen to your body. You only need to menstruate when you want to prepare to ovulate.”

She thought about it for a while, then suddenly it was obvious. She could just feel it.

“I really am a little girl again.” She wasn't sure about this. All the individual steps had seemed attractive, but the total was weird.

“No more than I am. No more than you were three weeks out of every four. Not that anyone not your doctor or lover would know unless you tell them. And only as much as you want — just kick off a cycle on the first of every month if it makes you feel better. Or think of it as simply skipping all the discomfort and hot flushes of giving it up.”

“Perhaps.” She turned to the window. “It is a glorious day out there, isn't it.”

“Spring, near summer. Bound to add a lift to the spirits when coming from autumn. We have some leisure time for the moment — we can walk, have a picnic, whatever. A lull before rejoining the fray.”

13:00 UTC, 24 May 3342

“What now?”

Carolyn stared out into the blue sky with just a few wisps of high cloud, feeling pleasantly weary after exercise, and refreshed after eating. She lay stretched out on the grass, head pillowed against a small outcrop of rock, at the summit of the island.

From the rooms where she had woken up, they had emerged onto short grass and dry dust under the trees, and walked under the shade, in the cool breeze, dappled with shafts of sunlight that were warm on the skin. Everywhere was birdsong, and flashes of colour showed the singers. Brightly coloured butterflies too, and small animals darting across the ground, and climbing into the branches above.

After a short while, they came to where an outthrust ridge of rock extended from the central heights almost to the rim.

“We're headed for the top,” Nancy explained, “A bit of a scramble to get you used to the new corpus. It's six hundred meters up, some walking, some climbing. I've organised food for when we get there.”

And so Nancy had started to climb, scrambling up the rough rock, to stand at the crest of the ridge, and wave her on. The ascent was an easy one, half climb, half hands and knees, but by the time she had reached the crest, Nancy had moved on, walking along the ridge, where the Sun shone through the gap it made in the tree cover, illuminating her against the shadowed background. She had dressed herself slightly more appropriately for the exercise, in halter top, shorts, and walking boots, and Carolyn appreciatively watched the muscles working in those bare legs, before checking the state of her own outfit. She expected to see scuffing on the leather where she had placed weight on her knees, but the surface was unblemished, just as were the toes of her shoes. She shrugged, and shifted some material to make nigh backless gloves for later clambering, and followed where Nancy had led.

In stages alternately of walking, often in the wildlife dense shade of the trees, and climbing easy scrambles on sunlit bare rock, they had ascended to the very summit, Nancy taking the lead, Carolyn following.

She didn't know how Nancy was faring, but she was definitely feeling the exertion, hot, legs knowing they had done plenty of steps, ready for something to drink. But for all that, exhilarated, an awareness that all her major systems were well within acceptable bounds, the closest to an amber on the board being the first marginal effects of altitude, the starting point, two thousand feet below, having been over a mile high. It seemed so natural to have that awareness, but then she realised that it was something new, part, she guessed, of the upgrade.

The last leg was a climb from out of shadow, the sky concealed by leaves, into the wide sky, and then a few feet more, and she crawled onto the wide flat top, perhaps five yards across, ringed with bare rock, and slightly sunken, an open and grassy space. On the grass, Nancy already sat, a blanket spread beside her, with a hamper open, showing an array of stuff, a jug of something pale and cloudy, and two glasses already deployed from it.

Wordlessly, she took the glass that Nancy held out to her, and drank. It was crisp with the fresh acid sweetness of fruit that has just attained ripeness, and beneath that, the vaguest suggestion of salt.

“That was very welcome. What else have we been given?”

“Cheese, tomatoes, olives, apricots, bread. A loaf, a jug of… well not actually wine, and thee. Or was it thou?”

“‘Dum dee-dum dee-dum Paradise enow’, I think, so must be thou.”

“Translating the words myself from my mother tongue, I have to guess at subtleties like that.”

Carolyn sat down on the blanket, and tore herself a chunk of the crusty white bread, and of the pale crumbly cheese, and fashioned a makeshift sandwich. Holding it in one hand, a tomato in the other, she began to eat.

It was perfect, like the memory or the anticipation of the first simple meal of a holiday in France, the bread light, the cheese soft, creamy, with just enough lactic tang to avoid cloying, the tomato juicy and salt-sour.

But on another level, while she revelled in the primitive pleasure of simple food, well prepared, she considered Nancy's words, and her response.

“Are you trying to hint something, with that particular quotation, and then that walk in the moonlight crack earlier?”

“Well, think about it. You've been spirited away by a little grey space alien. What do you expect?” Nancy grinned, wickedly as she said that.

Carolyn's heart skipped a beat. It seemed so obvious, stated like that. Frantically, she tried to recall the various urban legends she had heard recounted.

“Don't worry too much,” Nancy advised, concern replacing the levity, “I was only trying to make a joke out of a strange coincidence between my appearance and one of the myths of your time. And anyway, the whole anal probe thing is just not my sort of turn-on either.

“It's just that I'm not used to dealing with people who don't know the Clan's reputation — we are still notorious across much of human space. As usual, a kernel of truth has been exaggerated into the stuff of myth.”

“And this affects you in some way that is relevant?”

“Yes. We — the Clan Wolf — are in some respects a human bee-hive. We — the clan in general, not myself personally, we've augmented our numbers over the centuries by occasional — usually in batches of a dozen or so every two years — parthenogenetic conception. It's not quite cloning, as there is usually some tweak for improvement, or adaptation to current environment done. Growth to term is almost invariably done in a tank, though there have been a few pregnancies in our history, and all but a handful of us are, as I put it before, worker bees, sterile females.

“It's not common social model, which may reassure you, but equally we aren't bees, we retain the bulk of our human ancestry. Not coming into season, but being continually, uh, interested. And in a context where the Clan was isolated unto itself, socially at first, and later in extended interstellar flight, in the slowboat from Lindisfarne to Starbow, there was only one thing that could be done. Existing tendencies were reinforced and designed in to the Clan's standard template.

“By the time we headed on the fifty lite haul to Luthien, we were already notorious, something that just added to the other, unfortunate, bits of our history. On Starbow, colonists wouldn't quite lock up their women when Clan terraforming teams were working in their area, but the suspicion was always there.

“At least when I was young, when we were long settled and out of the mainstream of planetary development, that one wasn't being thrown in our faces.”

Carolyn swallowed the mouthful she was chewing.

“Well that's as long-winded a way as I've heard of coming out of the closet. I don't suppose I have any such secrets from you. It would be in the history books, wouldn't it?”

“Yes. It is.” Nancy looked down, concentrating on serving herself some lunch.

“Was that why you contacted me first, rather than anyone else?”

“It was a factor. The number of key individuals, given the date of my arrival, was not large. And I needed honesty and sympathy in both directions. No secrets — I can't allow myself to hold things back if I'm also reading your mind. I can't stop that any more than you can stop hearing or smelling. And I have so much context to my life that stems from the years of history that lie between us.

“It doesn't have to lead to anything physical.” She paused. “We have already exercised, and there is food.”

And now, stomach comfortably filled, Carolyn lay in post-prandial repletion, posing a question that had grown an extra meaning during the meal.

Nancy, nibbling at an apricot, looked up.

“In broad, we wait for the Seraphim to send us back to your time. And then the hard work resumes to bring the Ascension, though at least for that I have gained some more material aid.

“Or is that not the sense I was supposed to take?”

“Neither, really.” Carolyn paused, staring into the blue, “I was still trying to figure out what I was doing here. What the next step in the argument was. What it is that I'm supposed to be fighting for or against that is different from anything I would have done.

“Not that I'm not grateful for this —” she held out her arms, now tanned to a light caramel colour, “ — but I don't see how it connects.”

“OK, if you want a quid pro quo, there is something you can do for me — I want to address the conference on the second morning. And I need you to back me up.

“You saw the Seraph, you know that things have changed. And yet in the lands beneath, like where we arrived on Earth, things are little different from what they were four thousand years ago. Iron Age subsistence farmers once again make up the population of Britain, as they were when Rome was by custom just being founded.

“There are towns and cities elsewhere on the planet, between the areas ravaged by the fading remnants of the Ascension War, and by the long legacy of industrialisation. And many more Romes will arise, small empires, tens of millions of people over large fractions of continents.

“The children of Earth are spread to the stars, and more have gone where we cannot follow, into the Ascension; but those scraping their livings beneath us are locked into a long, slow decline. They don't have the resources of energy to re-industrialise — only firewood and slave labour. The abundant coal that still lies under your home island, for example, is too deep for their mining.”

“Don't the Seraphs do anything to assist?”

“No. On their own, they are only human level entities, and have only those capabilities leased to them by the Ascended. They can't change the world by themselves, any more than I can. And the Ascended are inscrutable. They have very little contact with this physical world, only information can pass from whatever state they have entered and our state of being.

“It still amazes me that my petition was heard. There must be something deeply significant about the idea of reworking the original Ascension, that furthers their ends. I was told that this was necessary. And if it works, there will be no stay-behinds.”

“So what are you doing it for? Why did you start this off in the first place?”

“Looking for somewhere to belong. I'd been exiled — quarantined, really — cut adrift from home and family. That was eighty odd years ago. Even then, I had the idea of going to Earth. I wonder if it is all some plot of the Ascended, something they programmed into the family genome when they gave it to Mother Trixy in preparation for the first flight to τ Ceti, knowing that eventually one of the descendants would be separated from the Clan, and return with this idea.”

Carolyn felt sudden horror.

“If you could have been programmed, what have I let myself in for? What might they have built into me?”

“I cannot say. But even if you had refrained, something might have been in the air, to similar effect, or something might have been rewritten. Even if the Most High are unable to act directly, they could certainly tracelessly, and without arousing suspicion, subvert any human level mentality even if all they could do was send perfectly formed bits to a teletype. All we can do is try to be true to our selves of the instant.”

“OK, set that aside, then. But I still don't see what it is that you think you are trying to achieve.”

“It all starts to sound like religion, when you put it into words. The promise of something better than this universe of happenstance and evolved beings. Following the hint of something akin to apotheosis in the state which the Ascended have attained. Seeking Paradise. Satisfying that continual hunger that is life, dissolving into an Ocean of being, world without end.

“But not just for me alone, but for the whole of Humanity, or at least one cohort of it. An end to all the need in the world.”

The sadness Carolyn remembered from before crossed Nancy's face, as if she were trying to convince herself of the meaning of her cause.

“How do you square this with what you were telling me — let's call it last night — about time travel?”

“That everything that could happen is out there somewhere in configuration space? It's hard to do. If infinite salvation and infinite damnation are both out there, and histories can pass through either or none; if free will is meaningless because in a way we take every choice; then keeping any motivation is hard. All you can be sure of is that if you find yourself in a history where you have given up, gone with the flow, it's less likely that you'll be going through a good outcome state any time soon.

“I suppose it also answers the question about the Seraphim striving to aid the unascended survivors below — this, the state we are in as I speak, is by trivial demonstration, a possible state, and histories must flow through it. Even if we could redeem every possible sentient entity, that fact would remain.

“Stripping away the hypocrisy, I suppose my goal is indeed ultimately selfish, and ultimately futile — not all histories through this point end in apotheosis. Some must end in extinction, or worse. Perhaps even the path to Ascension leads through some form of annihilation, rather than any apotheosis, of my — of any — human level identity.

“I don't know, I don't even know if the answer is a knowable thing to intellects of our scale.”

“I should have read Cervantes, I guess. It certainly looks like I'm going to be in the Sancho Panza rôle on this trip.

“So, what next?”

© Steve Gilham 2002